Introduction

THE WHAT

The practice of issues management is occasionally confounded with “spin doctoring” – downplaying or putting out a less-than-candid narrative in an attempt to appear better in the eyes of the public, particularly when you find yourself in reputational trouble.

That’s not what issues management is about.

In fact, most definitions of issues management are organized around the core idea that it’s a strategic management process used to detect, protect, explore, and close what issues management expert Teresa Yancey Crane described as gaps between the actions of the organization – specifically a corporation – and the expectations of its stakeholders.

Responding to issues in today’s digital marketplace is both an anticipatory “mindset and a process.” It is an essential aspect of risk management and leveraging opportunities.

Establishing a method by which your organization routinely looks for, evaluates, and develops informed decisions and action plans is industry best practice these days.

THE WHO

As a key strategic function of the organization, establishing a team structure, roles and responsibilities, and accountabilities are the foundation of any issues management process. If your organization has more than one department or unit, then your issues management group ought to include representation from all parts of your organization. That representation should be senior enough to make decisions on behalf of their department and to bear the responsibility for carrying out decisions of the group.

Within the issues management group, communication with stakeholders will always be a part of any action plan, so your communications leaders need a seat at the table, but group leadership ought to belong to those in your organization who either have the most knowledge of the issue at hand or have most to lose if an issue is missed or mismanaged.

Given its significance to your business, ensure you keep a direct line of sight on this team, their process, and their outcomes. Provide issues management leaders with your clear support.

As Henry Kissinger is attributed as saying,

“An issue ignored is a crisis invited.” It is possible to “make good” out of a crisis, particularly if it is viewed as an opportunity to build reputation, change the conversation, and alter perception. However, as an issue moves through its life cycle, there are more voices to manage, more attention is being paid, and there tends to be more urgency required on your part.

Making good decisions in this context is not easy. Repeatedly making decisions in this context is the equivalent of firefighting, which drains energy and resources from your team and business.

Here is a simple example:

The pandemic has significantly changed the landscape of work. Your organization needs to decide whether it remains a virtual workplace or employees are called back to the office. On multiple fronts, the successful resolution of this issue will have an impact on your business, so you remain responsible for the outcomes. You invite your senior HR person to lead the group around the management of this employee issue and charge your operations or finance leader to support the HR leader with relevant information on impact to the bottom line, facilities, technology requirements and so on. Your communications leader coordinates with HR to develop supporting key messages and provides access to appropriate communications channels and opportunities. Everyone reports to the CEO to outline their analysis of the issue, decisions, and implementation plan. The CEO signals their support for the group’s decisions by actively participating in the implementation plan.

THE HOW

Consider issues management as a hybrid of risk management and business development. By its very nature, issues management is an anticipatory exercise and therefore requires an anticipatory process. This anticipatory process has seven key steps:

- Monitoring

- Identification

- Prioritization

- Analysis

- Decision-making

- Implementation

- Evaluation

Step 1: Monitoring

Monitoring is just another term for being aware of your business environment. Making it common practice to scan what is being said, written and done by public, media, interest groups, government, and other opinion leaders in relation to your industry, service or products can reveal a situation or change with the earmarks of an emerging issue for you. Look to see whether what you are observing on the horizon exhibits any of these criteria:- Is the issue growing in significance? Who is bringing the issue up? As an issue grows in public legitimacy, it is likely receiving the increasing notice of journalists and other opinion leaders.

- Does what you are seeing in the distance offer a quantifiable threat or opportunity in terms of your organization’s markets or operations? And,

- Is this issue you see in the distance gaining the championship of a group or institution with actual or potential influence? This criterion applies equally to internal dynamics. For example, potential layoffs have become part of the employee buzz.

Step 2: Identification

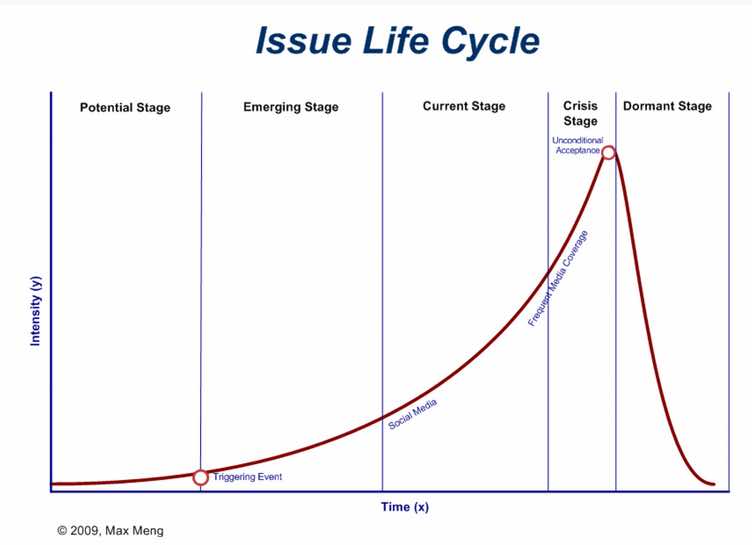

Former University of North Carolina communications professor and now a consultant at Rowland PR, Dr. Elizabeth Dougall, argues that issues have a lifecycle comprising five stages–early, emerging, current, crisis and dormant. In simple terms, as the issue moves through the first four stages, it “attracts more attention and becomes less manageable from the organization’s point of view.”

Done correctly, however, issue identification during the first three stages can often turn an emerging issue into an opportunity. For example, looking to differentiate itself in the crowded burger market, A&W recently began selling 100% Canadian grass-fed beef, tapping into a growing anxiety around climate change, the environmental impact of raising beef cattle and global supply chains. Currently, the burger market in Canada consists of A&W, Burger King, Dairy Queen, McDonald’s, Wendy’s, and Harvey’s, and A&W is the second largest, as well as the fastest-growing burger chain in Canada.

So how do you decide what is an issue to be monitored and what is an issue that needs action?

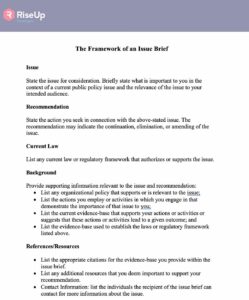

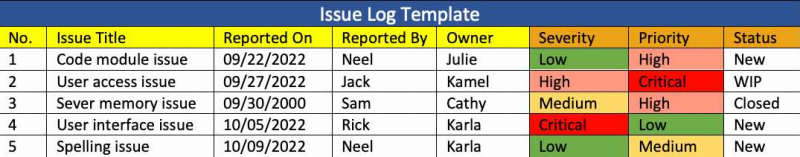

There are several tools your organization can apply to bring clarity to this question. One such tool is an issues log (see figure 1).

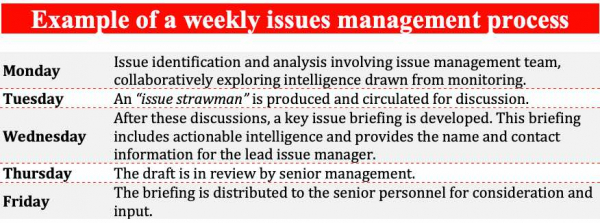

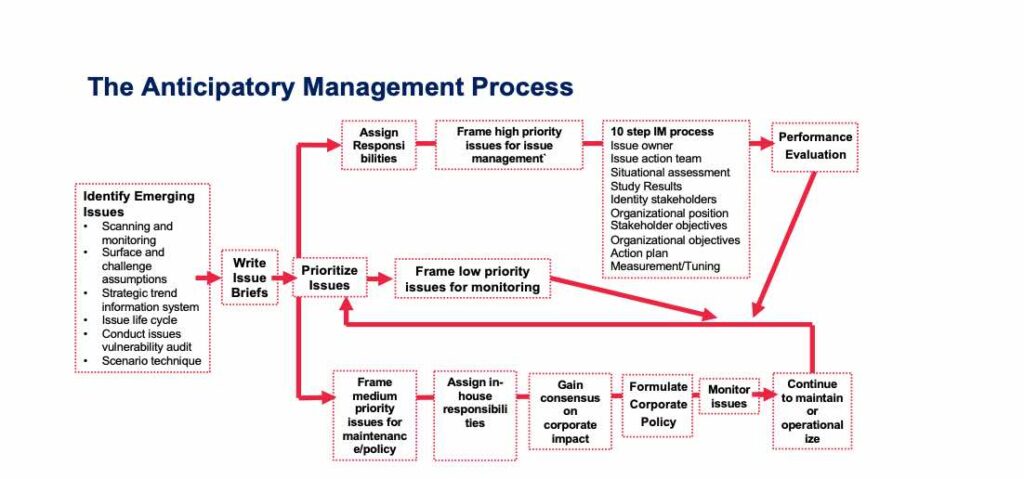

Another useful issue management tool is the “Issues Brief,” explained in figure 2. Figure 3 outlines a process. In all cases, to be valuable and relevant, the process and tools you use must be managed, routinely applied, and regularly reviewed.

What is an Issues Brief:

The issue brief is a short, written document that states the issue for consideration, indicates a recommendation for action, provides supporting information relevant to the issue and recommendation, lists references for the supporting information and other resources as necessary, and provides contact information.

To be effective, the length of an issue brief should be no more than two pages, back-to-back. (That is why they are sometimes referred to as “one-pager.”)

If the issue brief is to be used among members of an organization, the information presented in the issue brief should be consistent with and reflect any organizational overall mission/mandate. The information presented in an issue brief is often the same information used in the development of an organization’s advocacy agenda.

Step 3: Prioritization

By this stage in the issues management process, a lot of quality information has been gathered around potential emerging issues, but you cannot launch an action plan for all of them.

How do you decide which issues require your attention and resources to be applied?

There are several questions you can ask as part of your triage of potential issues. For example:

- How widespread is this issue? (How far-reaching will its impact be on our product, service, sector, company, industry?)

- How great is the risk/reward? (“What is at stake—Profit? Reputation? Freedom of action?”)

- How probable is it? (“What is the likelihood of this issue becoming a reality for our organization?”)

- How pressing is this issue? (Is it fast-moving or slow?)

The point of note here is that no two issues are equal and should not be treated as such. As part of an organization’s routine process and structure, issues can be moved up on the agenda for action or back to continued monitoring, depending on prioritization.

One significant caveat:

When prioritizing these issues, look at the answers from not only the external perspective but also the internal one. Your employees are a rich source of issues management information and very often will be implicated in your organization’s response. How likely is the issue to affect your employees and their perception of the organization? How much impact will the issue have on them? Whenever there is a gap between the organization’s actions and employee expectations, business performance, corporate reputation and business development efforts can be diminished, and issue management efforts can be undermined.

Step 4: Analysis

So now you know which issues are a priority, but how should you proceed?

Analysis is what converts all your gathered information into useful intelligence that your issues management team can use to chart the best course of action given what is known.

Here are a few questions you can use to further break down and better understand an issue:

- What are the most important details of this issue?

- What are possible solutions to address this gap between the organization’s actions and stakeholder perceptions?

- What are the plausible outcomes of these different options?

- Who are the stakeholders and what will satisfy their concerns? And in what order can these concerns be addressed? Who are the allies, the opposition, neutrals?

- How might they react? [Tip: there are some great digital marketing resources out there, such as psychographics, to provide insight into your stakeholders beliefs, values, and goals.

Step 5: Decision-making

During the analysis phase, you are breaking information down into smaller components. In the decision-making phase, you bring those pieces back together into an informed, clear, and singular objective.

Strong issues management requires laser focus and often the collaboration and cohesion of many different employees/teams contributing to the objective. A too complex or less-than-clear objective allows too much room for independent activity and disagreements, which can weaken or derail your issue response.

If your issues management group comes back to you with a loose objective or too many objectives, take it as a red flag that perhaps the internal alignment is not yet where it needs to be.

Before proceeding to implementation, firmly establish an informed, clear, and singular objective for your management of a particular issue.

Step 6: Implementing the plan

This phase is basic project management, with someone holding the accountability for developing and managing the plan directed toward achieving the identified objective.

Who is the lead?

The issue determines who leads. As noted above, your issues management lead should always be a senior team member with the most knowledge of the issue or the one with the most to lose if the issue is managed poorly. Your team lead needs to be designated with the authority to direct the resources of the organization with your support. Different issues will have different leads.

What needs to be part of the plan?

- The timeline and resources needed.

- Specific actions to be taken. Deliverables required. By whom? When? With whom?

- A comprehensive and aligned communications approach that outlines the key messages, audiences (including internal audiences!) and channels, and timing.

Step 7: Evaluation

If you think of issues management as a one-time event, you will be relieved when the issue passes, but you will have missed a major opportunity.

Issues management is a process, and the more you learn and practice, the better you will perform next time. And there will almost certainly be a next time.

Working with your issues management team, start with the big picture. And invite feedback from all corners.

- Did the organization meet its objective relative to this issue?

- If so, what factors contributed most significantly to meeting this objective?

- Did you get drawn off-course at any point? If so, why and does the reason tell you anything? Were you able to course correct? Did it work? Why or why not?

- Did you fail to achieve the objective? What factors contributed most significantly? Was the objective itself off course? How could we improve our objective setting?

Then, taking a deeper dive into the components of your process and planning:

- What lessons can be drawn from the failures and successes of the issue management plan?

- Evaluate any policies, practices or programs created in response to the issue. Were they effective? Do they need revising?

- Monitor positive/neutral/negative responses on a timeline. Did you get the responses you anticipated? Did these responses come when you expected? Do the responses tell you anything about the management of this issue?

- Track and analyze media inquiries and social media engagement. Quantity? Tone?

- Take the pulse of your target audiences, including internal audiences (see Step 3!).

Finally, to further embed the concept that issues management is a part of everyone’s job, consider issues management as a Key Performance Indicator (KPI) for all employees. This is another way to embed issues management into your organization’s DNA. It provides a framework for routine feedback and coaching as required, and in many instances, issues management offers an opportunity for new leaders to step up, which further strengthens your corporate “issues management” muscle.

In today’s world, it’s just a part of doing business.

“Indifference is expensive. Hostility is unaffordable. Trust is priceless. It’s all about relationships.”

-Ted Rubin, Social Media strategist and author.

Case studies

Case Study 1 – United Airlines: Gone wrong

The crisis: The conflict occurred in United Airlines flight number 3411, which departed from Chicago to Louisville on April 9, 2017. Before passengers began boarding, it was announced that the flight was overbooked. United needed to put their employees on this plane. So, they asked for volunteers to give up their seats in exchange for $400 US, a free hotel room and a ticket for a flight the next day. No one volunteered. When boarding was complete, it was announced that four passengers had to leave the plane. Again, no one volunteered, so the company decided to choose passengers randomly. Two of the passengers left, and one refused. The one who remained said that he was a doctor and needed to get to his patients. When he refused to leave the plane, he was forcefully dragged from his seat and was struck in the process. The crisis started when a cell phone video recording of the incident was published on social media.

The response: When United realized that they couldn’t get out of the scandal, the CEO Oscar Munoz commented on the situation. He apologized for, “having to re-accommodate” the customer. This statement provoked a new wave of crisis. United’s social media audience accused him of being disrespectful and of misidentifying the cause of the problem. Instead of apologizing for forcing the passenger to deplane, Munoz apologized for his inconvenience.

The best line: “The apology by the CEO was, at best, lukewarm or, at worst, trying to dismiss the incident,” Younger said. “The CEO should make a better, more heartfelt, more meaningful and more personal apology.”

The reactions: United was blasted on Twitter. The company’s social media audience was indignant. They satirized the situation, created memes and GIFs, and made jokes.

What’s more, United lost more than $800 Million in revenue. United wasn’t able to manage the crisis by themselves, and they had to hire a professional crisis management team.

The resolution: After losing $1B of it’s market value due to the scandal and resulting lawsuit United issued multiple apologies, changed its overbooking policy. Now, crew members can’t remove passengers already seated.

The CEO also met with the Chinese consulate in Chicago (Chinese investors are large shareholders) “over the possible impact to bookings” as social media users across the U.S., China, and Vietnam call for a boycott of United.

The takeaway: In United’s case, the CEO apologized, but his words caused even more indignation than before. Why was that? The instance that occurred on the plane was quite traumatic to those that witnessed it personally and those that saw it on video. It deserved a heartfelt response, but the tweet showed a lack of understanding and accountability. In United’s case, the CEO’s apology sounded as if he didn’t actually care, and their audience immediately felt it.

Online apologies must be carefully crafted. Think of the emotions that need to be addressed and consider your words carefully – “how could this be offensive”? An apology should not sound like a press-release. When a brand makes a mistake they need to own up to it and let the public know they are going to address it and ensure it never happens again.

When you are ready to apologize publicly, say it with passion and from your heart. Do not use formal language or sound like a typical press-release.

Case Study 2 – Apple gone right

The crisis: Following the tragic San Bernardino terrorist attack on December 2, 2015 where 14 people were killed and 22 wounded, the US government demanded Apple release a new iOS. The proposed system would have a back door that would give the government unlimited access to any iPhone user.

The response: Apple refused the demand with this very public letter.

The best line: “While we believe the FBI’s intentions are good, it would be wrong for the government to force us to build a backdoor into our products. And ultimately, we fear that this demand would undermine the very freedoms and liberty our government is meant to protect.”

The reactions: Apple’s letter sparked a public debate on the future of cybersecurity. The American public was divided on the issue, but a number of tech giants, including Google, Microsoft, and Facebook, stood by Apple and formed the Reform Government Surveillance Coalition.

The resolution: Apple stood by their decision and refused to create a backdoor. The iPhone was ultimately hacked after the FBI spent $1.3M on a secret tool. As of writing, the FBI has opted not to share the exploited weakness with Apple.

The takeaway: Put your customers first and communicate with friendly strength.

How do you stand up to a government and win over the public? By being bold, unapologetic, and unwavering. And, more importantly, by putting your customers first. Apple made it clear from the start that they opposed the government’s demand. Not for their sake, but for their customer’s.

Case Study 3 – Facebook’s clumsy issue management

The crisis: When it was revealed that Facebook was engaged in a situation of alleged data misuse by Cambridge Analytica, the world was shaken by the lack of transparency and eerie silence that followed the breaking news, capturing international headlines. Facebook faced a crescendo of questions this year about how user data has been harvested for political purposes. Investors dumped its stock over the risk the scandal posed to its business, CNN reported. The crisis continued through June with the news that Facebook has data-sharing partnerships with at least four Chinese electronics companies, including a manufacturing giant that has a close relationship with China’s government.

The response: The response from Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was slow and factually inaccurate – when he said that fake news didn’t influence the 2016 presidential election (he later flip flopped on that).

The best line: “The company turned what could have been a case of proactive issues management in 2015—when it learned of this data problem—into a full-blown, reactive crisis,” Vanessa Fioravante wrote for PR Daily.

The reactions: Some said Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg handled himself well during two days of Senate testimony. Others found him a tad robotic, as multitudes of mocking memes made clear. As a result 42 percent of Facebook users have decided to take a break from the platform—or to delete the app entirely.

The resolution: It’s still on-going – Facebook has made promises to root out fake news and be more transparent with data sharing but many see this as hollow. New York Times reported how federal prosecutors are “conducting a criminal investigation into data deals Facebook struck with some of the world’s largest technology companies.”

The takeaway: Facebook missed an opportunity to be an ethical leader as a result of this challenge. Look at how Nike behaved when they received backlash from having Colin Kirkpatrick as their new ‘Just do it’ spokesperson…they stuck to their values and weathered the storm and people respected them for it.